Carnivore or herbivore?

Newly discovered dinosaur called 'evolution caught in the act'

of dietary shift

David Perlman, Chronicle

Science Editor

Thursday, May 5, 2005

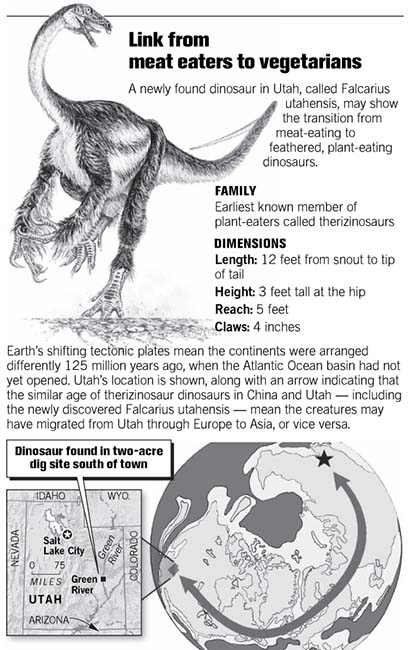

Fossil bones of a new tribe of feathered dinosaurs that

died by the hundreds 125 million years ago are giving scientists

fresh insights into the evolution of the lineage from fierce

carnivores to placid plant-eaters.

A mass graveyard on the side of a Utah mesa, where more than

1,700 bones have already been discovered, also shows the vast

range of the dinosaur world so long ago, when the drifting

continents of Asia and America were linked together as a single

land mass, scientists say.

After three years of digging, a team of University of Utah

paleontologists announced the discovery of the bizarre dinosaur

species Wednesday during a telephone news conference and in a

report being published today in the journal Nature.

It was "evolution caught in the act," said Scott Sampson,

chief curator of the University's Museum of Natural History as

he described the birdlike creature, barely more than 3 feet tall

at the hip as an adult and 12 feet long from snout to tail.

"An amazing evolutionary transition," said James Kirkland,

state paleontologist at the Utah Geological Survey.

Formally named Falcarius utahensis -- for "Utah sickle-maker"

because of its sharp, curved 4-inch claws -- the creature had

ancestors that were relatives of the voracious meat-eating

velociraptors of movie fame, Sampson said. Yet Falcarius is also

a primitive early member of the dinosaur group known as

therizinosaurs, some of which may have dined on fish as well as

plants.

The therizinosaurs are widely known from fossil beds in

China, but the Utah fossils are the first of the group ever

discovered in the Western Hemisphere, a surprising indication of

their wide range. And whether the Utah creatures were still

eating meat or had given it up in favor of plants -- or perhaps

were eating both -- is unknown, Sampson said.

However, he said, "With Falcarius, we have actual fossil

evidence of a major dietary shift, certainly the best example

documented among dinosaurs. This little beast is a missing link

between small-bodied predatory dinosaurs and the highly

specialized and bizarre plant-eating therizinosaurs."

The legs clearly were beginning to change from swift-running,

prey- chasing limbs to ones bulky enough to carry a larger body,

Sampson said.

The teeth show evolutionary changes, too, he noted, from the

sharply serrated shapes needed for cutting meat to broader,

leaf-like shapes that were better for shredding leaves. And the

gut was changing, expanding to a size big enough for fermenting

plants to make them digestible.

But the feathers on Falcarius were really "proto-feathers,"

said Lindsay E. Zanno, a Utah graduate student and member of the

excavation team. "The feathers obviously did not evolve for

flight. They may have existed at first for regulating heat, or

as mating signals, or as camouflage."

Just how the dinosaur form changed from predator to

plant-eater still poses a mystery, Sampson said, and speculating

about the problem "means working outside the realm of science."

But Falcarius, clearly descended from meat eaters, may well

have emerged on the scene when the environment was changing, too

-- from a landscape dominated by ferns and pines to the advent

of flowering plants on a large scale, Sampson said.

"Here was a new edible resource to be exploited," he said,

"an open ecological niche, perhaps, that may have made Falcarius

become a devoted vegetarian."

To Kevin Padian, a leading paleontologist at UC Berkeley, the

Utah discovery is highly significant -- both for providing fresh

evidence of the transition from meat-eating to plant-eating in

the dinosaur lineage, and for demonstrating the geographical

spread of the life forms on what have at times been widely

separated continents.

From the presence of Falcarius fossils in Utah, however, it

now seems clear that the varied therizinosaur species was spread

across both Asia and North America at a time when the two

continents were joined and the beasts and their descendants

could migrate far and wide.

"It shows an evolutionary connection of life between the

continents," Padian said. "There was lots of back and forth, and

it's been a two-way street, so the more you look, the more you

find."

The dinosaur site was excavated and tunneled on the side of a

mesa near the south central Utah town of Green River, and it has

already yielded enough bones to account for hundreds, if not

thousands, of bodies.

But its rich trove, which Kirkland found in 2001, might never

have been discovered at all if it hadn't been for a confessed

criminal.

A professional fossil dealer in Moab named Lawrence Walker

had sold some bones from the site to a Denver collector,

Kirkland recalled, and when Kirkland was introduced to the

dealer in 1999, he told Walker how important they were.

"Once he figured out he had a new dinosaur, he realized

scientists should be working the site," Kirkland said. "His

conscience led him to get his stuff to me."

It was illegal to dig at the site without a permit, however,

and Walker was indicted in November 2002. He pleaded guilty,

served five months in prison and paid a $15,000 fine.

Kirkland, Sampson, Zanno and all their colleagues are

properly permitted -- and they're still digging on the mesa.

Page A - 2

URL: http://sfgate.com/cgi-bin/article.cgi?file=/c/a/2005/05/05/MNGTBCK6SV1.DTL